Abstract:

Sometimes the standard dental examination fails to evaluate all aspects of the patient's oral health. This article provides insight into what constitutes a complete examination and makes suggestions on the necessary elements for comprehensive diagnosis and treatment.

In sports, a player such as Brett Favre, Peyton Manning, Kobe Bryant, or Tim Tebow can be said to be the "heart and soul" of the team. In the business model, companies fashion their mission statements to be their heart and soul. In dental practices, mission statements serve as the guiding principle for the practice and typically state that the team commits to providing quality, comprehensive oral care and the best possible treatment for patients. However, for many practices, this promise misses the target when pulling the best treatment "off the shelf" and delivering it to their patients. At the core of a dental practice is a complete examination: this, along with comprehensive treatment, is what dental practice mission statements promise patients.

The problem lies in a practitioner's perception of a "complete examination" and what the examination should entail. Many clinicians perform oral evaluations similar to what was learned in dental school or what their colleagues do. The problem is the disparity between what is being done and what patients deserve. A thorough, complete examination can be the true core of a practice and, if followed, can enable practitioners to fulfill their office mission statement of providing comprehensive care to all patients. This article provides the dental professional with the concepts and techniques to incorporate a complete examination into his or her practice.

If a group of dentists were queried to determine how many of them do complete examinations, most would say all their new patients receive one. Yet how "complete" is this examination, and, if it is not already complete, why would any dentist want to change to something more involved and time consuming? Without a definitive reason, most dentists would not change their standard practice: however, this article will discuss the ways that a complete examination benefits both the patient and the practice.

A complete examination can:

- identify patients who have signs and symptoms of masticatory system instability such as temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease, uncoordinated muscles, pathologic wear, and fractured teeth.

- discover a lack of anterior guidance to protect the posterior teeth.

- identify centric relation interferences and working and balancing side interferences that can disrupt all systems of oral health, such as joints, muscles, and teeth.

- identify signs of mobility, recession, abfractions, and teeth with furcation involvement.

- discover oral cancer.

- discover lesions of endodontic origin.

- detect caries.

- consider all aspects of esthetics that may encourage the patients to enhance their smile.1

Few patients receive an examination as complete as outlined in this article. But when it is performed, a patient may state: "This is the most thorough exam I have ever had in a dental office."2 Patients, whether or not they have the interest or resources to accept the treatment recommendations provided after a complete examination, may be impressed by the thoroughness taken to evaluate and educate them on their dental health.

This process can also have powerful benefits for the dental practice. A complete examination can:

- allow the dentist and team the time to build relationships with a new patient.

- build trust from the patient toward the practice for its concern and thoroughness.

- enable the dental team to provide the patient complete treatment once the principles of complete dentistry are incorporated into the practice. The practice can shift from the "drill and fill" mentality to that of treating the patient comprehensively through splint therapy, equilibration, creating the anterior guidance, and determining a complete restorative treatment plan. The prescribed treatment presented is proactive, not reactive , and addresses treating the causes of breakdown, not the effects.

- build a practice of loyal, appreciative patients who refer friends and family.

Evaluating Masticatory System Stability

During the examination process, it is recommended the clinician works with the patient to identify the signs of instability and discusses the implications of problems that remain untreated. Once all the information is gathered, a comprehensive treatment plan to restore the patient to optimum oral health can be created.

The complete examination has seven parts to evaluate masticatory system stability. To begin, obtain a thorough patient history. As stated earlier, this is the time to start building a relationship with the patient. Gather information as to how the patient was referred; personal information about the patient's family, work, and hobbies; dental health goals and interests; and where the patient is on the continuum to "optimal oral health." 1 A patient history includes a medical history, medications, dental health, comfort, function, and esthetics. The patient should be encouraged to ask questions during the examination, and a mirror or an intraoral camera should be used to show the patient signs and symptoms of health or instability.1 It is important for the practitioner to demonstrate evidence of healthy aspects of the patient's oral status and not focus only on the problems.

The second part of the examination involves muscle palpation. A thorough understanding of the muscles of the masticatory system is necessary for evaluation of occlusal muscle problems. 2 An overworked muscle will be tender or sore to touch. The patient will either squint or report soreness on palpation. To palpate muscles, walk the index and middle fingers from the origin of the muscle to the insertion (Figure 1).

The first group of muscles to palpate are the elevator muscles, which are located behind the teeth and elevate the condyles, holding them against the eminence while hinging the jaw. Palpate the masseter, deep masseter, temporalis, and medial pterygoid. The medial pterygoid can only be palpated intraorally (Figure 2). In evaluating the tenderness of the medial pterygoid, place an index finger on the pterygomandibular raphe and press laterally on both the right and left sides. If the elevator muscles are tender to palpation, look for interferences in lateral excursions during the occlusal evaluation.

If the patient has soreness or tenderness in the group of muscles that are responsible for the horizontal positioning of the mandible, look for interferences in centric relation during the occlusal evaluation. The superior head of the lateral pterygoid retains the disk's proper alignment with the condyle during function. The muscles in this group to palpate are the digastric and lateral pterygoid muscles (Figure 3). The digastric muscles are easy to palpate; however the lateral pterygoid cannot be directly palpated. To evaluate for tenderness of the lateral pterygoid, the practitioner should place a thumb on the patient's chin and have the patient protrude the mandible against the resistance provided by the thumb.

The last group of muscles to be palpated are the postural neck muscles, which are the sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitus, and trapezius. These are antagonists to other muscles: if there is tenderness on palpation, it can indicate the muscles are not working harmoniously, which could be related to excursive interferences.

As the practitioner palpates the muscles, the assistant should record the results. If a muscle is tender on palpation, the dentist should be thinking how this muscle functions and what is causing its hyperactivity.

The third component of the examination is to evaluate the mandible's range of motion. Two factors can cause limited mandibular range of motion: muscle contraction and joint immobility. The patient should be asked about any history of limited range of motion.

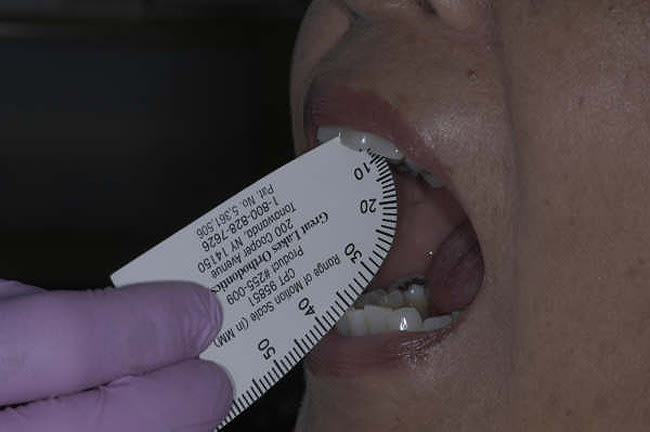

The first motion to evaluate is to have the patient open as wide as possible and close. Some patients will have limited opening due to discomfort. If this is the case, ask them to open until they begin to feel discomfort and measure the amount of opening. For maximum opening, the normal range is 40 mm to 50 mm plus any overbite that is present (Figure 4). Also, evaluate for any deviation on opening and closing. If the mandible shows deviation, it may indicate limited translation of the condyle on the side of deviation. Wiggling movements on initial opening can be related to disk displacement as the condyle attempts to recapture the disk. In addition to noting the degree of opening, the practitioner should also observe left and right lateral excursions and protrusive. In measuring lateral and protrusive movements, the normal range is 7 mm to 15 mm.

The fourth part of the examination is a joint analysis. The patient should be asked about any history of joint discomfort, locking open or closed, noises such as clicking or popping, difficulty chewing certain foods, bite changes, or teeth shifting.

Three locations are used to palpate the joint externally. Place fingers over the joint in the area of the lateral pole, and have the patient open and close. Tenderness in this area can indicate inflammation or damage at the lateral distal ligament. Next, have the patient open and palpate the fossa distal to the condyle. Signs of tenderness in this area can indicate ligamentitis. The third site to palpate is the opening to the ear canal. Place the smaller fingers in both ears and press anteriorly as the patient is opening. Tenderness can indicate inflammation in the posterior ligament.

The last test for the joint is load testing in centric relation. Centric relation is the relationship of the mandible to the maxilla when the properly aligned condyle disk assemblies are in the most superior position against the eminentia irrespective of vertical dimension or tooth position. 3 At the most superior position, the condyle disk assemblies are braced medially, thus centric is also the midmost position. A properly aligned condyle disk assembly in centric relation can resist maximum loading by the elevator muscles with no sign of discomfort. Using bimanual manipulation and applying three levels of pressure (gentle, medium, and heavy), the dentist asks at each level if the patient feels any sign of tension or tenderness (Figure 5). There are four possible reasons for a positive load test: 1 improper technique by the dentist, tenderness in the lateral pterygoid muscle, displaced disk, and joint pathosis. In either TMJ, if the patient has signs of tenderness at any level of pressure, reposition the hands and repeat the process. 4 If there is tenderness on load testing, the muscles may need to be deprogrammed, using cotton rolls in between the teeth for 5 to 10 minutes. Then, proceed again with bimanual manipulation to load test the joint and evaluate each level for any signs of tension or tenderness. Once the patient shows no sign of tension or tenderness, the dentist, with the joints seated, slowly brings the teeth together to determine the first point of contact. This can be verified by articulating paper. Record this information for future reference to verify accuracy of the mounted study casts. Finally, reseat the joints and close the patient to the first point of contact. Once the patient feels the first point of contact, have him or her raise a hand and hold that position. Then instruct her or him to squeeze the teeth together to maximum intercuspation. Observe and record the direction and amount of slide from centric relation to maximum intercuspation.

The recording of any centric relation to maximum intercuspation discrepancy is important to have when mounting study models with a facebow and centric relation bite record5 (Figure 6). The mounted study casts on the articulator should match the recorded information that was observed in the mouth. If not, new centric relation bite records should be taken and the study casts remounted.

Another test, Doppler auscultation, is used to evaluate sounds such as crepitus in the joint and works by amplifying the noise. Sounds that occur in the first 20 mm to 25 mm of opening (rotation of the condyle) indicate a displacement of the disk at the medial pole of the condyle. A sound that happens during translation shows there are changes occurring at the lateral pole of the condyle.

Information gathered during the complete examination may indicate the need for imaging of the joint. Use of a computed tomography (CT) scan is considered when joint pathology is suspected. CT allows frontal and lateral views of the condyle, as well as views of the medial and lateral poles, making it an excellent tool for diagnosis. If the position of the disk on the medial and lateral poles needs to be evaluated, the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would be indicated.

The fifth part of the examination is the occlusal dental examination. Centric relation is considered the foundation for predictable dentistry.1 As previously described, record the first point of contact, direction, and amount of the slide from centric relation to maximum intercuspation. Record the most anterior tooth contact in maximum intercuspation.

There are five requirements for a stable occlusion: 3

- Stable holding contacts on the maximum number of teeth possible.

- Anterior guidance in harmony with the envelope of function.

- Immediate posterior disclusion in protrusive.

- Immediate posterior disclusion on the working side.

- Immediate posterior disclusion on the balancing side.

Record the signs of occlusal instability for each tooth such as wear, mobility, vertical and horizontal fractures, and drifting of teeth. Recording this information helps the dentist understand if all systems are working harmoniously.

At this point in the examination, an evaluation of the patient's periodontal health is completed. Record pocket depths on six sites for each tooth present. Document the sites that bleed on probing, recession, mobility, furcation involvement, gingival attachments and contours. The practitioner can determine if occlusal instability is contributing to periodontal breakdown and help establish whether the patient needs to be referred to the periodontist for evaluation before determining the final restorative treatment plan.

The sixth part of the examination is the oral cancer screening. Evaluate the floor of the mouth, cheeks, lips, tongue, hard palate, soft palate, and upper and lower vestibules for any lesions or changes in tissue health.

The final part is imaging. The Dawson Academy recommends a series of 21 intra-and extraoral photographs 6 These views allow the dentist to evaluate all aspects of the patient's esthetics and provide a tool to communicate with the patient and laboratory technician. A high-quality full-mouth series of radiographs, panoramic radiograph, or any other type of imaging are essential for this complete examination.

Conclusion

From this discussion, it is obvious there are skills that the dentist must know for performing a complete examination (Figure 7). The practitioner should have the ability to confidently perform bimanual manipulation to seat the joints in centric relation.3 To mount the study casts on an articulator, a facebow and centric relation bite must be used. The dentist must understand splint therapy, equilibration, anterior guidance, and envelope of function, to name a few areas. In addition, the general dentist should assemble a team of specialists with similar treatment philosophies to discuss and determine the best restorative treatment plan for the patient.

As Peter E. Dawson, DDS, says, "Start with the end in mind." 1 The general dentist is the quarterback in this process—the one who gathers all the information in the complete examination and crafts with the patient and all involved specialists the final restorative treatment plan.

This article has noted a possible discrepancy between the way examinations are given by many practitioners, and this outlined complete examination. A study and mastery of complete dentistry is required to put all the pieces of this puzzle together: fortunately, general dentists have access to a many hands-on educational opportunities in a number of venues. Once learned, this comprehensive examination and "complete" style of dentistry will be incredibly rewarding for the dentist as well as the patient. The dentist now has "on the shelf" all the tools needed to treat the patient comprehensively.7 It is at this point that the practitioner is truly following his or her practice's mission statement, and the complete examination becomes the "heart and soul" of the practice.

References

1. Dawson PE . Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems . 2nd ed. St. Louis , MO : Mosby; 1989:1-13.

2. Polansky B. The Art of the Examination . Cherry Hill , NJ : Private Practice Publications; 2002:205-221.

3. Dawson PE . Functional Occlusion from TMJ to Smile Design. St. Louis, MO : Mosby; 2007:3-9.

4. Dawson PE. Functional Occlusion from TMJ to Smile Design. St. Louis, MO : Mosby; 2007:277-306.

5. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1989:238-268.

6. Pace S. Digital photography: the first step in the record-gathering process. Vistas Complete and Predictable Dentistry . 2008;1(1):11-13.

7. Wilkerson D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Masticatory System Problems. St. Petersburg, FL: The Dawson Center for Advanced Dental Study; 2002.

About the Author

Laura E. Wittenauer, DDS

Private Practice

Newport Beach, California