Ronald C. Kobernick, DDS, MScD

In the author’s experience, the dentists who are most successful in having patients agree to treatment are those who gather the most thorough diagnostic records. Proper records are vital to consistently achieve long-term, predictable, and stable results that maintain excellent occlusal, functional, and esthetic results and tissue health. Consequently, it is essential for each team member to be versed in acquiring adequate clinical information so that all significant findings can be assessed before and during treatment. Dentists who understand the significance of information gathering and who communicate effectively with the patient about their findings will have more success in treatment and case acceptance.

The same records that the author gathers as a periodontist are largely required by the restorative dentist. Some of the most valuable information is gained prior to the clinical examination, when the patient is interviewed. The goal of this preclinical meeting is multifold: an introduction of the dentist to the patient, and the dentist’s beginning to establish a relationship with the patient to create an atmosphere of trust, understanding, and compassion. Further, it is an opportunity to understand the patient’s dental background and his or her awareness of specific dental issues; to identify emergencies that must be handled prior to comprehensive treatment; to begin to understand treatment motivators; to identify “blockers” that might prevent treatment; and to clarify any medical issues that might necessitate modifying treatment or its extent. Frequently, a physician should be contacted regarding medical issues that might place the patient at risk, or to determine medical stability.

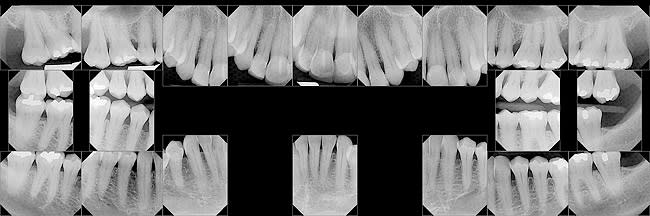

A current set of complete radiographs should be available before beginning the clinical examination. The radiographic series should consist of five maxillary anterior films, three mandibular anterior films, and two posterior films in each quadrant. Two vertical bitewing films on each side complete the series. The advantage of vertical bitewings is that they allow the interproximal osseous margins to be visualized with minimal distortion, which helps identify areas of osseous loss.

The radiographs are evaluated to identify carious lesions, the presence of endodontic lesions or inadequate previous endodontic treatment, areas of osseous loss, furcation involvement, impacted teeth, inadequate or failing restorations, and areas of pathologic osseous lesions. Panoramic films can serve as an adjunct to the series of intraoral films to screen for pathology. They are not adequate to use as the only source of radiographic evidence to determine the presence of periodontal osseous loss and to identify areas requiring restorative treatment. The final piece of information to be gleaned from the radiographic examination is an initial analysis of implant needs. Missing teeth that need to be replaced or those with poor prognoses should be noted.

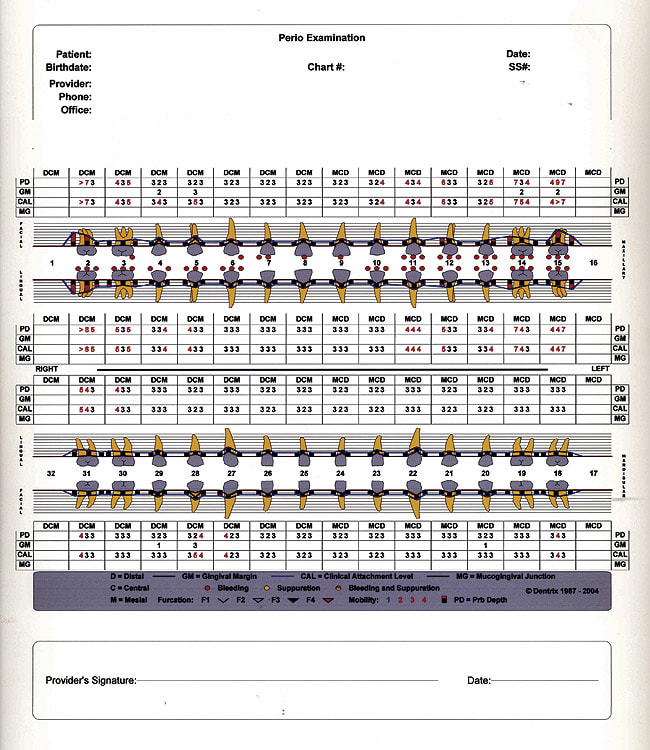

Figure 1 is a representative complete set of radiographs illustrating severe osseous loss affecting Nos. 2 and 15, significant angular osseous defects mesial to Nos. 3 and 14, a horizontal osseous defect between Nos. 11 and 12 (note the change of coronal osseous height between the Nos. 11 and 12 interproximal space and the normal Nos. 12 and 13 area), and a subtle osseous change in the interproximal space Nos. 21 and 22. The change was related to the presence of a gingival cyst, which was biopsied. The probing record in Figure 2 is of the same patient represented in the radiographs.

During the clinical examination, the patient’s blood pressure should be recorded. The dentist plays an essential role in contributing to the maintenance of the patient’s health.

The intraoral examination follows. An oral cancer screening should be completed, examining and palpating the tongue, cheeks, lips, and floor of the mouth and noting any changes affecting the hard and soft palate. Any abnormalities should be recorded and recommended for biopsy as appropriate treatment dictates.

The periodontist and restorative dentist must understand the health of the patient’s periodontium to effectively diagnose necessary treatment. Periodontal probing of each tooth is essential to understand the patient’s needs. In addition to measuring six spots on each tooth (mesiofacial and mesiopalatal, midfacial and midpalatal, and distofacial and distopalatal), the periodontal probe should be “walked” along each surface to detect any narrow osseous defects between the probing points. When probing interproximally, keep the probe perpendicular to the occlusal plane to achieve accurate recordings. In addition to identifying pockets (any subgingival spaces 5 mm), note subgingival inflammation as bleeding points. The presence of furcation involvement and the extent of involvement, categorized as Grade I (up to 3 mm of horizontal involvement), Grade II (between a Grade I and Grade III involvement), or Grade III (through and through osseous loss), should be identified. Because differentiating between Grade I and II furcation involvement is rather arbitrary and teeth with “early” Grade II involvement have a better prognosis than a more involved “later” Class II involvement, it is appropriate to record the horizontal extent of probe penetration into the furca to allow a more precise diagnosis (ie, 5 mm facial furcation involvement).

While probing, identify mucogingival defects (areas of is the probing record of the patient whose radiographs are presented in Figure 1. Severe osseous loss (pocketing of > 6 mm) affects Nos. 2, 14, and 15. Moderate-to-severe pocketing (6 mm) is related to No. 12 mesial, with moderate pocketing (5 mm) affecting Nos. 3, 13, and 31. There is no furcation involvement of Nos. 2 and 15 because of the fused roots present. Multiple bleeding points are noted, illustrating generalized maxillary inflammatory changes.

An occlusal analysis should be completed. Findings to be highlighted include joint pathology characterized by pain, joint sounds, or limited mandibular movement. Occlusal interferences in centric relation, lateral jaw movement, and anterior guidance, mandibular “slide” into centric occlusion, tooth mobility, fremitus, or tooth migration should be characterized.

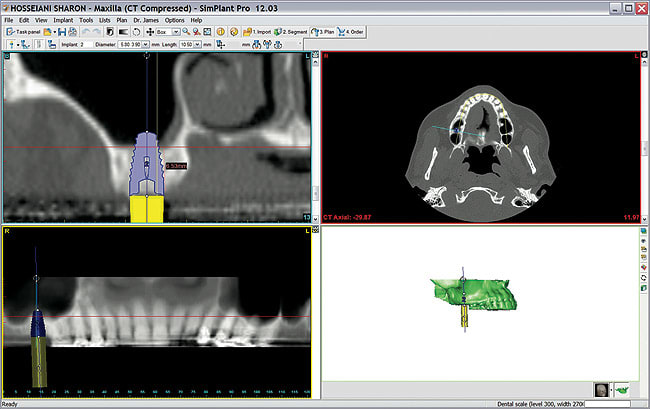

The last piece of information to be gleaned from the examination involves an analysis of implant needs. Thus, missing teeth or those with poor prognoses should be noted, with an initial consideration of whether the ridges are deficient in width or height, available space, position of adjacent roots, interocclusal space, occlusal implications, and proximity to the maxillary sinus(es), mandibular canal, or mental foramen.

Mounted centric relation models should be taken if there are occlusal, restorative, orthodontic, or implant considerations. A series of intraoral photographs consisting of a retracted view to show the anterior segment and then with decreased magnification to show teeth to at least the bicuspid segments; right and left buccal mirror views; and maxillary and mandibular occlusal mirror views should be included in the records. Periodontists may take additional intraoral views focusing on the mandibular anterior tissues if recession or mucogingival defects are present, and an additional photograph of the maxillary anterior/bicuspid tissues if there are considerations of gingival harmony. Extraoral photographs are essential—smiling and unsmiling frontal views of the face and smiling and unsmiling profile views as well as a close-up of the profile of the lips and teeth showing the inclination and projection of the teeth and the drape of the lips. Finally, direct-on photographs of the lips and teeth at rest, smiling, and pronouncing the “E” sound complete the series.

In addition to the mounted centric-relation models mentioned previously, additional records should be taken by the implant surgeon, consisting of a 3-dimensional (3-D) view of the implant recipient site(s). The computed tomography (CT) scan, translated into SimPlant® (Materialise Dental NV, Leuven, Belgium) or similar software views, is used to specifically analyze the appropriateness of the site for which implants are planned. The software allows 3-D, cross-sectional views of the ridge to determine whether adequate ridge dimension is present and to identify proximity of the implant to the sinus and/or mandibular mental and mandibular nerves; panoramic views to evaluate mandibular nerve position and proximity of the sinus; a 3-D representation of the mandible and/or maxilla to view the exit inclination and position of the implant(s) in relation to adjacent and opposing teeth; and visualization of the osseous housing supporting the implant in horizontal slices from the apex of the implant to its prosthetic platform. In addition, the software allows implants and restorations to be placed virtually to clarify the appropriateness of the anticipated implant position in considering space requirements of the implant within the edentulous ridge and to adjacent implants and teeth. The models and scans are instrumental in eventually constructing surgical guides to ensure optimal implant placement. Figure 3 illustrates a typical SimPlant scan with four “tiles.” The lower left view is a panoramic view, with the upper left tile a cross section of the area in question. Note the panoramic view appears to show adequate vertical osseous height for implant placement in the No. 2 site while the virtual implant placed in the cross-sectional view clearly indicates the need to augment the apical area with an osseous graft prior to placement of the anticipated 5.8-mm wide x 9.0-mm long implant. The upper right tile allows viewing the osseous tissue surrounding the implant along its entire length, while the lower right tile is an anatomic view of the surface characteristics and dimension of the implant site and the implant’s emergence profile.

As important as the records are in allowing the periodontist/restorative dentist to diagnose problems, adequate time is also essential for using the information to develop a comprehensive treatment plan.

The case presentation, the discussion with the patient to share the information gathered and appropriate recommendations regarding necessary treatment, is the last component of the records process. It is beyond the scope of this article to speak about all the issues—psychological as well as motivational—when encouraging the patient to proceed with treatment according to the practitioner’s recommendations. It should be understood, however, that the closer the treatment team’s common vision of treatment goals, the greater the potential for the patient to accept the recommendations.

There are additional requirements for the team to perform maximally together. The referring practitioner should communicate with the specialist, preferably in writing, before the referral. The information should include a discussion of any issues that have been identified as positive or negative motivators. The restorative dentist should share a detailed, written treatment plan before the patient’s first visit with the periodontist to establish the referring dentist’s recommended treatment. The periodontist can use this information to reinforce the restorative dentist’s suggested treatment plan. It is helpful for the patient to hear the same recommended treatment from a second source. The periodontist, of course, should be free to add to the recommended treatment plan. Any differences in opinion should be resolved before the patient returns to the periodontist for the “diagnosis and recommended treatment” appointment. Often, the periodontist, restorative dentist, and other team members have developed a common vision of final results after having performed together in previous cases, so that everyone intuitively understands the recommendations of their fellow team member(s).

Once the periodontist has spoken with the patient about the recommended treatment, presented the fees, and explained the treatment sequence, the patient is referred back to the restorative dentist for the final treatment plan presentation. The periodontist should share with the restorative dentist his or her understanding of the patient’s commitment and any other pertinent information that would help move the patient toward agreeing to treatment recommendations.

After gathering thorough records, the periodontist, restorative dentist, and other team members are able to work closely to provide a thorough, well thought-out treatment plan to achieve the stated goal of long-term, predictable, and stable results. In beginning with a thorough diagnosis of the patient’s presenting clinical situation and developing a vision of the end result prior to initiating treatment, the four essential aspects of any treatment—excellent occlusal, functional, and esthetic results and tissue health—can be routinely and predictably achieved.

About the Author

Ronald C. Kobernick, DDS, MScD

Private Practice

Largo and St. Petersburg, Florida